Thursday, December 2, 2010

Remembering the Four Churchwomen

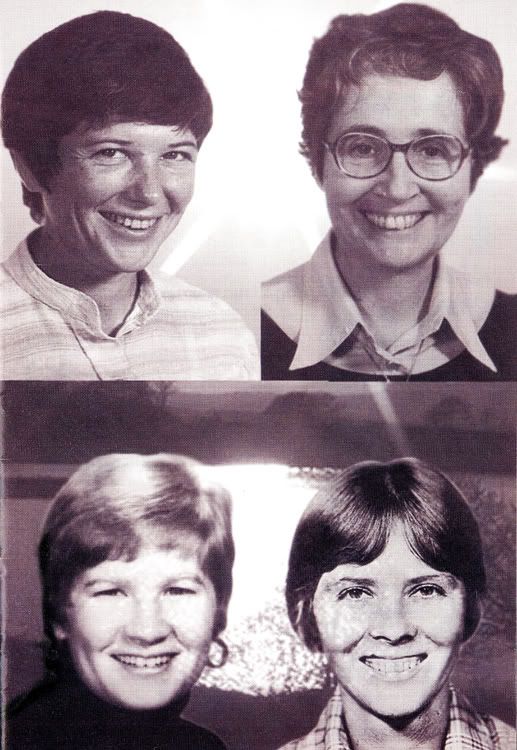

Remembering the Four Churchwomen

by Steve Schultz

If you’ve had the privilege of traveling on a delegation to El Salvador, you quickly become aware of the significance of martyrdom in Salvadoran culture and theology. Those who have given their lives in the struggle of the powerless for dignity are continually honored and called to mind. Archbishop Romero may be the most prominent example of this tradition, but we also have the six Jesuits at the University of Central America, Father Rutilio Grande, the more than 70,000 whose names cover the Wall of the Martyrs in downtown San Salvador, and the Four Churchwomen whom we recognize in our liturgy on December 5th.

While we have our own fallen heroes, most recently Martin Luther King, and John and Robert Kennedy, North American culture has no obvious parallels to the Salvadoran veneration of those who have died for the cause of justice. Thus it may seem like a morbid obsession to find the blood-stained vestments of Monsignor Romero or the bullet-riddled Bible of one of the Jesuit theologians on display when you visit El Salvador.

And yet, on spending time with people and hearing their expressions of gratitude, it becomes clear that these sentiments are far from morbid. What comes through instead is a sense of remembrance, in the face of great loss, of the presence and the goodness of this beloved person, whose life continues to inspire and illuminate the lives of others. We are brought back to the theme of accompaniment, a posture of ministry in which one walks with others, seeking to share in their lives and suffering. In this, Jesus represents the ultimate example, as one who was executed for joining with the cause of the marginalized in his society.

As we remember the Four Churchwomen, whose deaths contributed to a growing opposition to American participation in the war in El Salvador, we can seek to learn from their example of accompaniment. As Dietrich Bonhoeffer has written:

Christ, so the scriptures tell us, bore the sufferings of all humanity in his own body as if the were his own—a thought beyond our comprehension—accepting them of his own free will. We are certainly not Christ; we are not called on to redeem the world by our own deeds and sufferings, and we need not try to assume such an impossible burden. We are not lords, but instruments in the hand of the Lord of history; and we can share in other people’s sufferings only to a very limited degree.

We are not Christ, but if we want to be Christian, we must have some share in Christ’s large-heartedness by acting with responsibility and in freedom when the hour of danger comes, and by showing a real sympathy that springs, not from fear, but from the liberating and redeeming love of Christ for all who suffer.

Mere waiting and looking on is not Christian behavior. The Christian is called to sympathy and action, not in the first place by his or her own sufferings, but by the sufferings of his brothers and sisters, for whose sake Christ suffered.

From Letters and Papers from Prison

No comments:

Post a Comment